I’ve now lived in Israel for a little over two years. We arrived in June of 2021, excited to begin an adventure of unknown dimensions. It’s been extraordinary. Being an immigrant is impossible, thrilling, exhausting, and more. You have to learn a new culture even if you’ve visited many times—the tourist and the resident are two very different experiences. And though many Israelis speak some English and a few speak a lot, inevitably, you must learn Hebrew, the more the better.

Israel has one weekly and two annual sirens. The weekly siren announces the Sabbath. Here in Jerusalem it sounds forty minutes before the Sabbath begins. For those of us who observe the Sabbath, it’s an alarm that says finish up your preparations because it’s almost time for a different mode of living for the next 25 hours. It’s surprisingly quiet. Perhaps appropriately, it’s closer to a still small voice than an imperative command—a single tone akin to the note of a cello that sounds for a bit and then goes quiet. I don’t always notice it.

Then there are two annual sirens. The first memorializes the victims of the Holocaust. The second memorializes the soldiers who have died in Israel’s wars and the civilians who have been murdered in terrorist attacks. They both sound the same—a rising keening sound, again, a single note but more like a cry of pain than the soothing sound of the Shabbat siren. Both say the same thing. Stop. Listen. Remember.

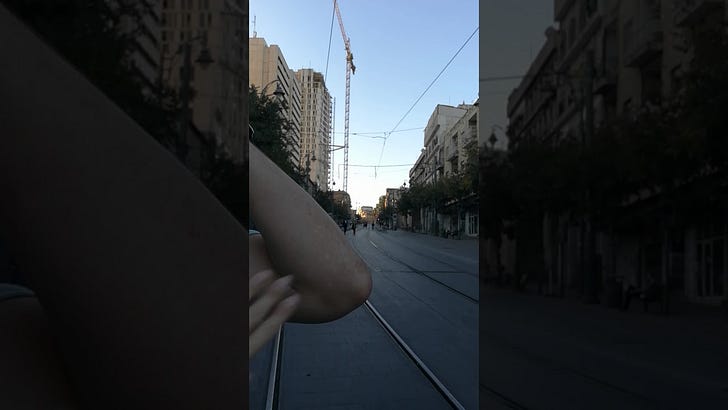

Memorial Day here is not a day of mattress sales and barbecues. Everyone stops, motionless, and listens to the siren. Even people in their cars stop and get out of their cars and stand in silence. Virtually no one goes about their regular business. Stopping and marking these deaths is a universal norm here. So many people here have lost someone close to them defending the Jewish state that such devotion comes easily.

On October 7th, I heard a different kind of siren. It was an oscillating wail I recognized because I have watched enough movies about London during the Nazi blitz during WWII to recognize an air raid siren. This siren says run. Seek cover. Keep your head down.

On that Saturday morning, which in Israel was also one of the happiest days of the Jewish calendar, Simchat Torah, my daughter-in-law—who with our son and 15 month old granddaughter were staying with us for the weekend—heard it or at least noticed it before I did. I was gathering up my prayer book and tallit—the Jewish prayer shawl—about to head out for the morning service at my synagogue. My daughter-in-law turned and looked at me with not a little alarm. That’s a siren she said.

I listened. I think you’re right, I said. Then we heard two dull thuds.

That’s a bomb, she said. I think you’re right, I said. Probably Iron Dome, I realized later, intercepting a rocket from Gaza which is about 50 miles from Jerusalem.

Shouldn’t we go to the bomb shelter, my daughter-in-law asked.

Uh, yes we should.

New houses and apartments in Jerusalem have what’s called a mamad, an acronym—merkhav mugan dirati—a protected or shielded residential space, a safe room constructed of reinforced concrete, an iron door, and with windows that will not shatter and kill you with broken glass if a missile lands nearby. Our apartment building is old. We don’t have a mamad. So we headed to the public shelter on the ground floor of a synagogue nearby that we go to from time to time.

Where you live in Israel determines how much time you have to reach a shelter. In Jerusalem, the time is 90 seconds which is a long time, sort of. It’s long because the missile needs to travel 50 miles, so where it’s headed becomes known a whole minute and a half before it reaches Jerusalem. We roused the household and headed a few doors away to the public shelter nearby. Half of us were still in pajamas. We joined a few other mamad-less families there along with the crowd there for the services.

The siren soon stopped its nagging, whining cry and we returned home. I went to services. A friend there told me a terrible rumor. That we had been attacked by Hamas from Gaza and that five people had been kidnapped. Israel has a bad history of kidnappings by its enemies. Google “Gilad Shalit” and you will learn that Israel goes crazy when a single soldier is a captive. Five people? We both shuddered. My friend reassured me—it’s just a rumor he said. We had no way of knowing that the number actually exceeded 200. The service continued as if nothing was wrong.

When the sirens sounded three or four more times that morning, we knew that something was very wrong. Soldiers on leave for the holiday were immediately called back to duty. My friend whispered to me that he had to step outside for a minute—his son had to return to his unit and was coming by to say goodbye. Having lived in America for almost my whole life until arriving in Israel two years ago, I had never had a son or daughter in the army. The idea that I would need to say goodbye on a sunny October morning to a son on the way to active duty, knowing little about the maelstrom he was about to enter, was something I could barely imagine.

When Shabbat ended, we began to learn the enormity and savagery of the pogrom inflicted on us. The death toll has risen steadily, not just because some of those injured that day did not recover. It has taken weeks to discover and identify all the bodies and to figure who was burned to death almost beyond recognition and who was kidnapped. The death toll is about 1500 people as far as we know now. Mostly Jewish Israelis but the deaths include workers from Thailand and some Arab-Israelis. A crude correction of this number for population size would mean the deaths of something like 50,000 Americans, 15 times the death toll of 9/11, roughly equal to all the deaths during the Vietnam war, but in a single day.

The next day we discovered that one our students at Shalem College, Amir Skoury, had been killed responding to the attacks, having rejoined his army unit to fight the invaders who had fanned out from Gaza into the souther part of Israel. Amir would have been a sophomore this year. He was an unusual student. Most of our students are 24 or 25 years old when they enter. He had been an officer and came to us at 30 years old. He left a widow and two young daughters.

His mother spoke at the funeral and mentioned how much he had enjoyed his year at Shalem and how precious had been their time together talking about the books he was reading. One of the other speakers was a professor at Shalem College, Ido Hevroni, who taught Greek Literature to Amir and his classmates.

In Ido’s eulogy he explained that in the Iliad, Hector, a commander of the Trojan army, is at the rear of the battle and his home is nearby. He takes the opportunity to spend a few precious moments with his wife and son. When he turns to say goodbye to his small son, the boy recoils at the sight of the terrifying warrior in his helmet and armor. So Hector removes his helmet, reveals his face, and speaks softly to the boy.

Ido explained that when Hector wears the helmet he speaks as a warrior, committed to the values of his home and homeland even at the cost of his life. When he removes the helmet, the man and the father are revealed. With broken heart, Ido explained that Amir, too, knew how to wear the helmet and remove it. After 12 years of service in the army, he put down his armor and helmet to come to college, revealing a charming man, a diligent and deeply curious student eager to understand everything he read, and a loving and devoted father.

Unfortunately, said Ido, because of the terrible circumstances forced upon us, Amir had to put on his helmet again and leave us. We wept at Ido’s words. And many of us who knew Amir well, are weeping still. War is hell, goes the saying, but words cannot capture the awful day that was October 7, 2023 and the unbearable pain so many people have already endured.

In the aftermath of that day, thousands of Israelis have come home to fight. More than half of our students have been called to duty, called back to their army units, putting on their armor and helmets and preparing to face on behalf of the rest of us, whatever comes next. A college without students is an oxymoron, so of course, the start of the school year has been postponed. But as I hope to describe in future posts, we continue to look for and find ways for the community of Shalem College to contribute even if there are no formal classes for the time being.

Since that first awful day, there have been a few other sirens and we have heeded them and run to safety. Elsewhere, closer to Gaza, the rockets are much more numerous. Those rockets from Gaza are toys compared to what Hizbollah in southern Lebanon is able to deliver—bigger and more accurate rockets, supposedly a stockpile of 150,000, that can reach anywhere in this small country to much more devastating effect.

So we listen for the sirens and if they go off again, whether from an attack from Gaza or Lebanon, we hope that Iron Dome can stop them or that we will reach the shelter in time.

And sometimes, to my dismay, I hear the sirens even when they are not shrieking—a car alarm or the sound of a car accelerating a few streets away can fool me, and for a moment, sometimes roused out of sleep and only half awake, I wonder if I need to wake my wife and sprint for the shelter.

Thank you for sharing, Russ. These stories and perspectives matter greatly. I hate the horror that you have all experienced and continue to face. My prayers continue. I've been listening to EconTalk since 2011, and honestly, you were one of the first people I thought about on Oct. 7.

Russ, I know that a typo is so minor compared to the material, but: "on the ground floor of a synagogue we to from time to time" should probably be "on the ground floor of a synagogue we [GO] to from time to time."

Condolences for the loss of Amir Skoury.