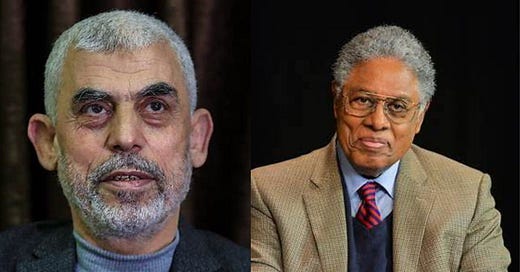

I almost wish Yahya Sinwar was still alive to see one of the greatest examples of unintended consequences in history.

Sinwar planned October 7th for years and he caught this country completely flatfooted. The immediate effect was quite extraordinary and nearly beyond his wildest dreams. 1200 dead. 250 hostages. A chaotic and ineffective Israeli response. But even most powerfully, he shook the confidence this country had in its fundamental ability to keep Jews safe in the Jewish homeland. He managed to stage a pogrom not in Czarist Russia but in modern day Israel.

He apparently had hoped for more. He hoped that the West Bank would also rise up and its people surge across the border. He hoped that Hezbollah would unleash some significant portion of its stockpile of 150,000 rockets, destroying and killing Israelis and further demoralizing us.

Those events did not happen. He did not reckon with Iran’s need for Hezbollah as a shield against an Israeli attack. Hezbollah kept its powder dry. The West Bank stayed quiet.

But still, October 7th was an operation that inspired many of his people and confederates and that struck terror into the hearts of Israelis. Can you imagine his joy and satisfaction at how what he had planned came to fruition?

And did he anticipate Israel’s response?

Surely he knew that Israel would respond. It always had in the past. But I don’t think he quite imagined the ferocity or resolve of Israel even as he held tightly to his hole card of the hostages, especially the children like the Bibas boys. He also knew that the Israeli response was a double-edged sword that would hurt Israel as well. With every death of a Hamas comrade came civilian deaths alongside those losses. I suspect he knew that those civilian deaths would mobilize world opinion against Israel and ultimately force Israel to stop short.

I don’t know if he imagined the sympathy he and his cause would receive on American college campuses. Some of that was presumably financed by his allies. But the size of it, and the role it played in slowing down Israel’s response under pressure from the Biden Administration was probably not anticipated, at least in its magnitude.

But the first lesson of October 7th is the cost of underestimating your enemy. Bibi Netanyahu grossly underestimated both the goals of Hamas and its ability to execute an operation in the name of those goals. All the evidence that Israel had that something terrible was brewing in Gaza was ignored. Hubris—overconfidence in technology and a misreading of Hamas—cost Israel greatly. This intelligence and strategic failure was unforgivable and stains Netanyahu’s legacy forever. The result was the worst single day in the history of Israel and one of the worst days in Jewish history.

Another man would have resigned. This one, perhaps, should have resigned. But hubris cuts more than one way. Bibi stayed on the job, damaged badly by his failure. So many people blamed him, so many people hated him already that he could not even appear publicly to lead his country as effectively as he might have. But for whatever reasons—shame, fear of a conviction for an ongoing case of corruption, overconfidence, narcissism, arrogance, hubris—he stayed on.

And as the war unfolded, it became clear that while Netanyahu had underestimed Sinwar and Hamas, this error was dwarfed by Sinwar’s underestimation of Israel and Netanyahu.

The soft tik-tok generation of young Israelis proved to be one of extraordinary resolve and strength. Young men and women, many with families, answered the call of duty serving as citizen-soldiers for hundreds of days in the aftermath of October 7. About half of my students at Shalem College have been serving since the beginning of the war. The war seems endless. But they return to fight for their country seemingly without complaint.

The world has judged these men and women harshly. They are called baby-killers, genocidal, full of blood-lust. Surely terrible things have been done by members of the IDF. War brings out our darkest side and our brightest. I know these men and women personally. Obviously, my assessment may not match yours. But ignore that for the moment. They, and their political leaders have not been deterred by the stories in the Guardian, the New York Times or on the BBC. So many of those stories turned out to be lies. Surely some are true. My point is simply is that we as a country and as an army have stayed the course despite the relentless and often dishonest vilification.

Sinwar and his allies did not foresee the resolve of Netanyahu or the soldiers of the IDF. And despite weekly and daily protests by Israelis as members of a free society demanding a ceasefire to get the hostages home, Netanyahu and his coalition maintained the impossible conflicting goals of eliminating Hamas and getting the hostages home. A lot of them have come home. Some from negotiation, some from threat of further destruction in Gaza. But the important thing to note is that Netanyahu has not deviated from his absurd double goal. Sinwar and his allied did not foresee this.

But the resolve of a citizen army and its leaders in the face of a relentless propaganda war might be the least important way that Sinwar underestimated his opponent.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that at least for now, Iran’s decision to restrain Hezbollah was the turning point of the war. This let Israel grind Hamas down from the air and then turn when the time was right to deal with Hezbollah. Sinwar obviously couldn’t have imagined the pager operation that disarmed Hezbollah’s leadership. But I don’t think he imagined that Netanyahu would have the guts to take out Nasrallah, which Sinwar did live to see, a month before his own death. The dismembering of Hezbollah removed a key shield that protected Iran and made what is happening now possible.

The world sees Netanyahu as a bloodlusting babykiller. A fascist. A right-winger at the head of a right-wing coalition. Here in Israel, until recently, he was seen a gutless pragmatist always willing to kick a tough decision down the road. That he would assassinate Nasrallah and attack Iran with the ferocity we have seen this week was unimaginable. Sinwar mistakenly saw Bibi as weak and ineffectual. Perhaps he was. Maybe October 7 galvanized him unexpectedly.

And now we come to the end game. Oh that Sinwar could see his patron, Iran, brought to its military knees in less than a week, Israel able to operate freely and destroy not just Iran’s military capability but to also pager-style, take out Iran’s military leadership and nuclear scientists.

So the first lesson of this war: don’t underestimate your enemy.

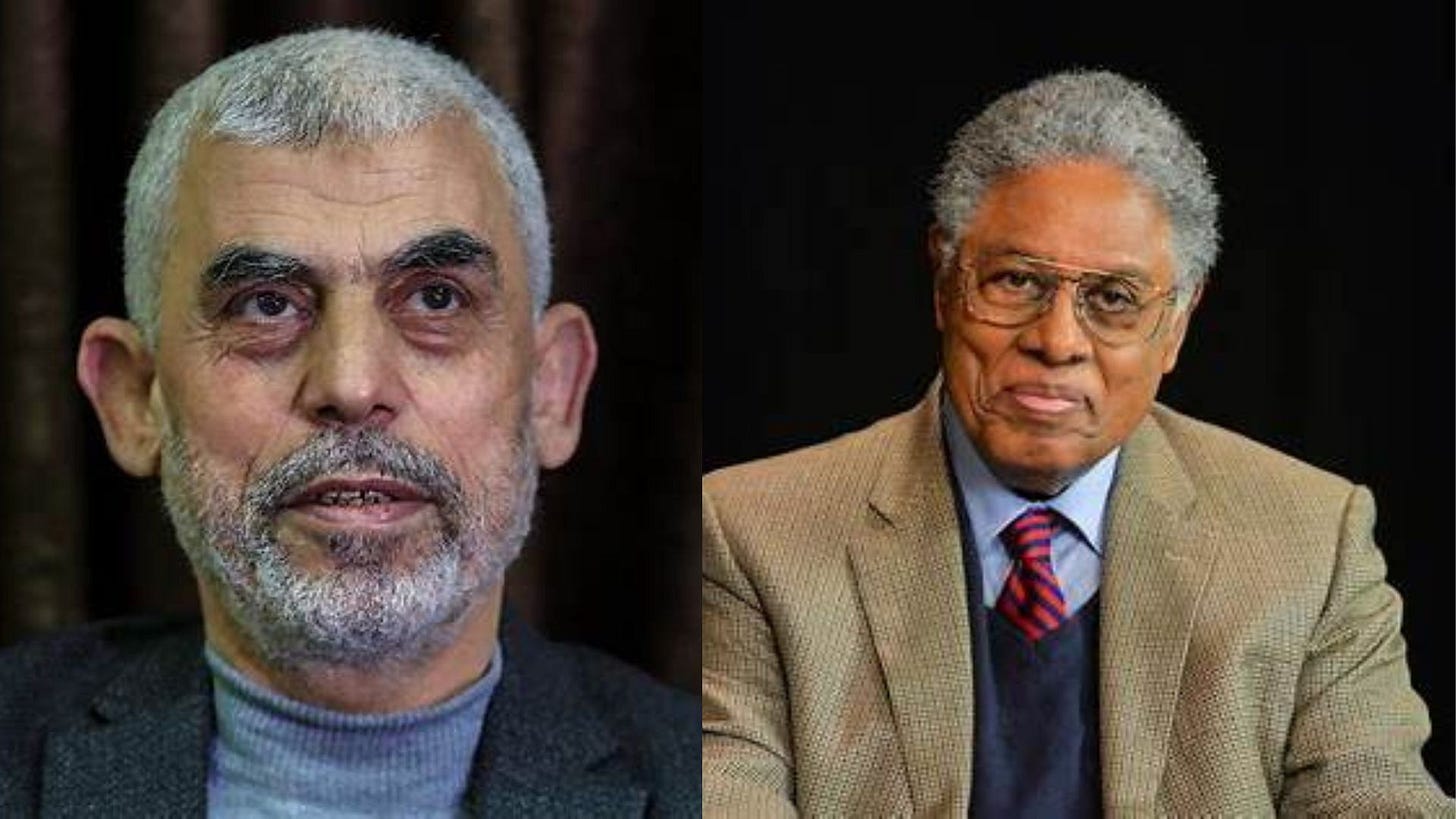

The second lesson is the great lesson I learned from Thomas Sowell. Whenever you consider a policy change or intervention, go beyond the immediate effects. Sowell credits his teacher Arthur Smithies of Harvard for teaching him this. The immediate effects may be attractive but then what? What comes next? What are the unintended consequences?

The great French economist and essayist Frederic Bastiat called it the distinction between the seen and the unseen.

In the economic sphere an act, a habit, an institution, a law produces not only one effect, but a series of effects. Of these effects, the first alone is immediate; it appears simultaneously with its cause; it is seen. The other effects emerge only subsequently;

they are not seen; we are fortunate if we foresee them.There is only one difference between a bad economist and a good one: the bad economist confines himself to the visible effect; the good economist takes into account both the effect that can be seen and those effects that must be foreseen.

Yet this difference is tremendous; for it almost always happens that when the immediate consequence is favorable, the later consequences are disastrous, and vice versa. Whence it follows that the bad economist pursues a small present good that will be followed by a great evil to come, while the good economist pursues a great good to come, at the risk of a small present evil.

I’m guessing Yahya Sinwar never read Sowell or Bastiat.

The visible effect of October 7 was glorious in the eyes of Sinwar. And many of the days that followed surely buoyed his spirits as well. Even the devastation of Gaza and the civilian deaths may have seemed worthwhile to him. After all, he built no bomb shelters there—just tunnels for his fighters. He put headquarters under hospitals and schools, forcing Israel to choose between military success and international disgust.

He should have asked “and then what?”

To be fair, only a truly great visionary, a prophet, could have foreseen what Sinwar set in motion, at least so far:

The likely end of Hamas’s rule of Gaza and maybe its suicidal missions to kill Jews and the Jewish state.

The liberation of Lebanon from under the thumb of Hezbollah and the possibility of it being a truly sovereign state un-menaced by Iran.

The fall of Assad in Syria.

The eradication of the military and perhaps political power of Sinwar’s patrons in Iran. A setback in their nuclear ambitions and possible regime change. We’ll see in the coming days.

October 7 was a dark day for Israel. The darkest of days. Its trauma will persist here for generations. Congrats to the monster who died waving a stick at a drone. But the rest of that monster’s legacy extends throughout the Middle East, and at least for now, that legacy is the destruction of much of what threatened Israel.

He should have asked “and then what.”

So three lessons.

Don’t underestimate your enemy.

Ask “and then what” when you see an attractive opportunity that appears to make things better.

The third lesson is yet another case of what Yahya failed to imagine:

Don’t mess with Israel.

October 7th set in motion a set of events that has made Israel the most powerful and feared player in the Middle East.

It’s June 17th, 2025. Israel is riding high. Netanyahu is on the verge of re-writing his legacy if he has not succeeded already. If I could whisper in his ear, I would whisper a single word: hubris. When you are riding high you are prone to think nothing bad can happen and that this winning streak is inevitable, deserved, and will continue indefinitely. That was Sinwar’s mistake on October 7. I hope Bibi knows that despite everything going his way for so long now, this moment is actually fraught with danger. As we move forward into uncharted waters with the future of Iran and the Middle East hanging in the balance, it would be wise to ask: and then what?

Russ,

This is a compelling use of the “and then what?” principle, and the narrative you build around Sinwar’s miscalculation is sharp. But one question lingers for me… not as a rebuttal, but as a continuation.

The essay applies second-order thinking clearly to Hamas’s choices, but less so to the present course of Israeli policy. If “and then what?” is a vital moral and strategic tool, should it not also be aimed forward? Toward the destruction in Gaza, the fallout of war with Iran, and the political future that might or might not be possible when the dust settles?

It is not a matter of moral equivalence. It is a matter of analytic consistency. The principle either applies across the board or it becomes a way of insulating one side from scrutiny while indicting the other.

The name of the blog, Listening to the Sirens, seems to gesture at this challenge. Odysseus did not defeat the sirens with cleverness or strength. He tied himself to the mast because he knew that seductive certainty would overpower his judgment. This raises a question. For someone living inside the conflict, personally connected to those fighting, and ethnically bound to the nation at war, how does one tie oneself to that mast?

That is not rhetorical. It seems like an honest, hard question for any Israeli thinker right now. How can someone stay tethered to long term reasoning and moral foresight when the sirens are all around… trauma, loss, duty, vengeance, solidarity?

If “and then what?” means anything, perhaps it must also be asked in the present tense. What comes after Gaza? What future is being made possible or impossible by these choices? What political horizon is left for coexistence? These are hard questions, and perhaps impossible to fully answer. But if second order thinking is worth doing, it cannot only be retrospective. And it cannot only be aimed at one side.

Thanks Russ . I am from the US and wish you and your family and your country well. Great that you live where you can write about your country’s leader in such a clear voice.